*This article has been updated since it was originally published in 2011*

Most large organisations offer their customers a large number of options such as government agencies promoting campgrounds in national parks, a university offering degrees, or an ecommerce company selling products. We are constantly presented with options, messages and suffer from information overload.

In this article, we set the stage for design lessons with an understanding of how human beings approach decisions and what it means to present people with overwhelming amounts of options.

Avoiding choice overload: Designing decisions for a great user experience

Usability testing that we have conducted at PeakXD since 2003 has really highlighted to us the importance of not bombarding users with too many options. In academic circles, this is known as choice overload. Many test participants, when presented with too many choices, such as holiday accommodation options, commented that they would abandon the site as they couldn't handle sifting through so many options.

There's been a lot of talk recently about why we make decisions the way we do and why humans are predictably irrational. They have even made a TV series, The Irrational, based on these principles which is airing on mainstream free-to-air TV in Australia. There are some very interesting takeaways for us to consider as designers, as we try to build experiences that send our sites' users away happy. Purchasing decisions are obviously a huge target for these lessons, but decisions on whether and how to engage with a website or product are made all the time as well.

We have two brains (OK. It's really one brain, with two processing pathways)

Most people know what is meant by "acting on their gut" - a common euphemism for the "emotional" brain, which makes fast and complicated calculations - versus using their "rational brain", which is slow, limited and calculates deliberately. These two different ways that we process information take place in different parts of the brain, and because I'm not a neuroscientist, I'm not going to attempt to explain.

What matters is that there are some things that are important for us to remember:

- We make decisions based on input from either of these processing centres (emotional / rational).

- Our emotional brain is wired to react quickly based on our past experiences.

- The emotional brain is efficient, but easily fooled.

The best decisions are NOT rational (at least not totally)

One of the most interesting patterns observed by researchers is that pure engagement with the rational, analytical mind almost always leads to less satisfying decision-making. For most of us, this doesn't compute. If we think things through, we're more likely to make good decisions, right? Well, that depends on how you define "good".

Although it's painful to acknowledge, our rational brains actually aren't that useful for making complex, multi-parameter decisions. We're great at making simple decisions with a limited number of variables to consider, but when it comes to juggling larger calculations we just don't have the conscious power to do this. The good news is that our emotional brain is pretty powerful - it actually does a pretty good job of crunching multiple variables based on our experiences. The emotional brain's output is felt rather than understood rationally. Usually, the emotional brain does a good job, but in situations with new variables that it hasn't met before, it doesn't always know how to give us the right feelings. Thankfully, since we have a rational brain, we can examine our gut decisions for glaring problems. To make good decisions, we need to trust our gut, but not too much.

In an interesting experiment with stock traders, the worst decisions were made when the traders were either completely dispassionate, with their conscious mind doing all of the calculating, or emotionally overwrought, throwing logic to the wind. Their most profitable trades were made when they were acting on a balanced platform of rationality and emotionality.

What this means for us: I think it's safe to say that we want our customers and website users to make the decisions that are best for them. It's no good to anybody to have someone leave your site after making a decision (or chain of decisions) that they'll be unhappy with. We can support good choices on the rational level by supplying only the qualifiers between options that are most important to users. Keep extraneous information to a minimum - some research should help to understand what information is important. On an emotional level, adhere to conventions as much as is reasonable to help people make decisions based on experience. Put some resources into a polished presentation, to eliminate distractions and make things feel comfortable.

Too many options can be a bad thing (but some choice is good)

Anybody who's done a fair amount of user/consumer research will tell you: People say they want choices, the more the better. Think of an ice cream counter. If you went up to an ice cream counter with just two flavours, you'd probably either leave, or be a bit annoyed at the limited range. In a sense, choice is power - the ability to steer your own fate. Generally, people find the act of choosing itself to be enjoyable.

The surprising part is what happens after we choose. While people have more fun choosing between larger numbers of things, they actually are happier about their decision when they've chosen from a limited set of stuff. Too many choices means increased likelihood of having missed a better opportunity - there is no way to really know whether you've made a good choice, because it's too complicated to parse all of the different options.

Decision-making is ultimately an act of comparison between choices. This takes some mental work, and it can be tiring or outside of our capacity to manage. If someone has too many options, they either make no choice at all, or adapt strategies to help them whittle down the number of viable options. Two common brain strategies for managing choice overload are

- Satisficing: Accepting only the first few options that meet some criteria, or

- Elimination: Ruling out options without consideration, to make it easier to compare the remaining options.

Clearly, either strategy can result in the decision maker either making a poor choice, or feeling as though they're unsure that the choice they have made is the right one.

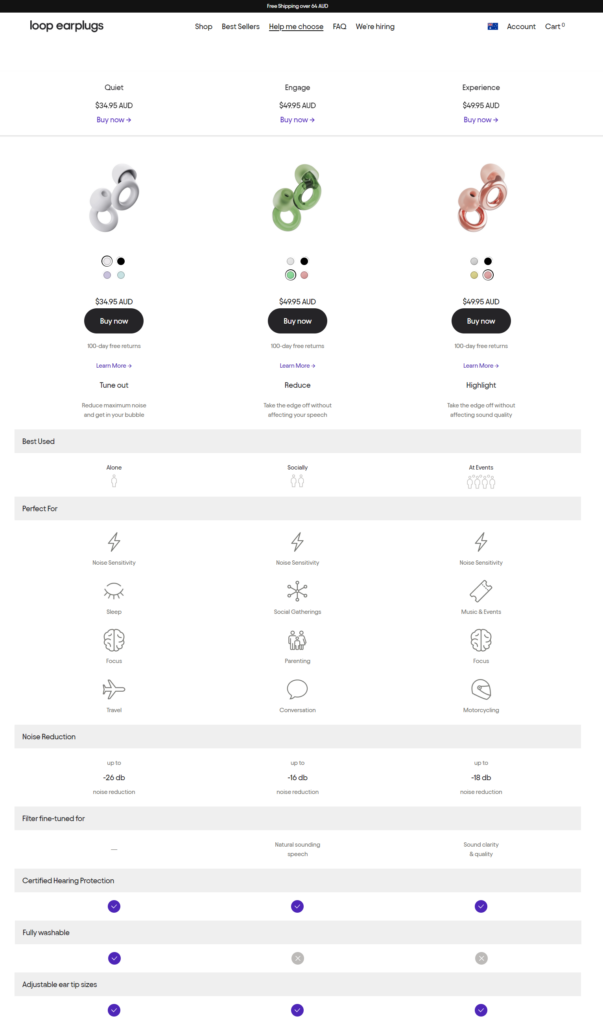

What this means for us: We can assist the rational brain in dealing with a large variety of choices by breaking out decision-making processes into filtering steps. When filtering a large pool of choices, start with simple choices at the outset - asking users to make complicated decisions without the context that can be provided by a few simple choices can be fatiguing. By starting simple, users will know that they've already started down a path that they're happy with.

From an emotional perspective, make sure the options provided to users speak to them on their level. Asking people to make decisions they're not comfortable with is counterproductive. As the emotional decision-making brain is guided by our past experiences, domain experts can comfortably answer much more complicated questions than novices.

In either case, limiting the options presented to users at the outset will probably help them feel better about their decisions. Asking someone to choose between 300 flavours of ice cream gets bewildering pretty fast. But maybe 20 isn't so bad, after all.

Decision making, like everything else, needs to be easy (mostly)

Enabling satisfying decisions can be a careful balancing act. It really depends on several factors: the weight of decision your users need to make, what their levels of experience and emotional investment might be, and the overall complexity of the choice to be made. If decisions are too complicated, people are likely to leave a situation worn out and feeling as though they've made a poor choice. If decisions are too simple, users may feel a lack of control and may simply not enjoy the decision-making process. To satisfy users, we want to give them the opportunity to make decisions that feel good on an emotional level while remaining acceptable to the rational brain. By following some of the simple recommendations in this article, we can work to make sure that users leave our sites feeling happy with the choices they've made.

Summary

- Use tools such as faceted search or filters to help users quickly rule out and eliminate a large number of options with little effort. kayak.com does a great job of this.

- Provide ways to prioritise, organise, compare and shortlist the vast number of overwhelming results/options.

- If you don't have the technology capabilities to implement the above recommendations, consider reducing the number of options available on your websites. Less is more. In usability testing of some of our clients' websites, we have had users comment that they would just leave the site when they are presented with too many options.

Sources/Further reading:

- How we Decide by Jonah Lehrer

- Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely

- The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz

- Colleen Roller's decision architecture column on UXMatters:

- The Impact of Choice Overload in UX by Eva Miller